In the land of Svalbard…

Introduction

As I promised, here is a longer post looking at the ichthyosaurs recently described (Druckenmiller et al. 2012), and more about palaeontological research, in the land of Svalbard. The original article, with descriptions and many images, can be accessed here, it’s open access . This post will be more formally set out for three reasons: (1) I’m trying a new program to see whether this can streamline my thought and writing (2) there’s been a lot of research, particularly recently, to come from Svalbard (3) I haven’t written at any length for a while, so I thought I should.

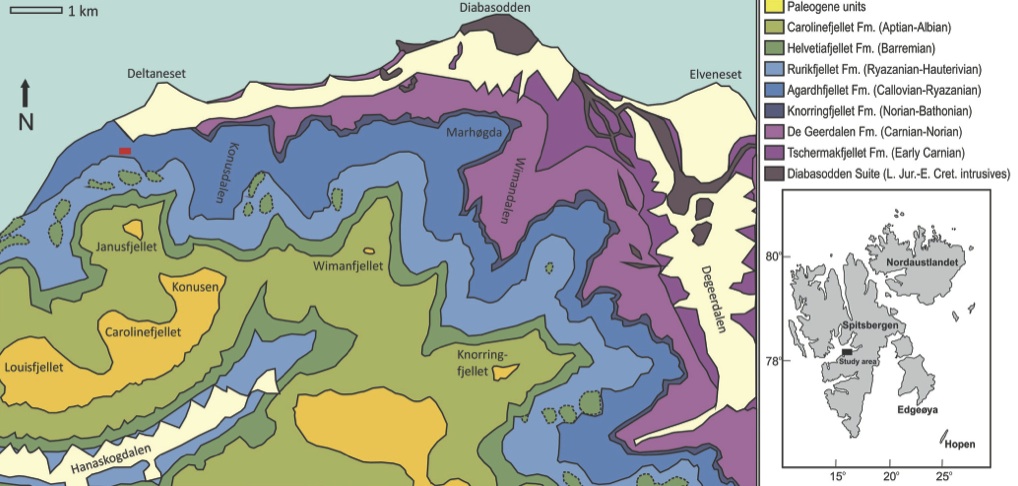

While the northern parts of the World have received much attention due to climatic changes (which are happening whether or not you believe this has been caused by human burning of fossil fuels), significant coverage by ice does not lend itself to geological fieldwork easily. Svalbard is an archipelago of Norway, 400 miles north of mainland Europe. The main island, Spitsbergen, is the largest and most inhabited of the archipelago, and where much of the research to be discussed took place. In the middle of the west coast of Spitsbergen, is the inlet of Isfjorden. The research took place on the southern coast of this, Northwest of Longyearbyen. The fieldwork recovered many fossils, identifying a new marine reptile lagerstätte — the Slottsmøya Member — and the recent Norwegian Journal of Geology has many papers on the plesiosaurs. In addition, there is an article on two new opthalmosaurids: Cryopterygius kristiansenae and Palvennia hoybergeti.

History of ichthyosaur palaeontology in Svalbard

Svalbard has been a haven of vertebrate palaeontology research for over 100 years. Much has been done on the Triassic material (Cox and Smith 1973). Some of the earliest collections were by Nordenskiöld in 1864 and 1868, and described by Hulke (1873). These included ichthyosaur remains for which Hulke erected Ichthyosaurus nordenskioeldii and Ichthyosaurus polaris (later referred to Mixosaurus (Baur 1887)). Wiman (1910) later reappraised this and erected Pessosaurus for Ichthyosaurus polaris and described four new species for which he created the genus Pessopteryx. Merriam (1911) commented on this, the scrappy nature of the material, and how Pessopteryx was similar in form to Omphalosaurus. It was also from the Triassic of Svalbard that Wiman described the then most basal ichthyosaurian taxon Grippia longirostris (Wiman 1929). From then until the 1980s, there was little work done on the ichthyosaur fauna of Svalbard. Mazin (1981; 1983) restarted this with work on Grippia and the probable ichthyosaur Omphalosaurus. At this time the main attraction of Svalbard, in terms of ichthyosaurs, continued to be the Triassic (Sander 1992; 1998; Maisch and Matzke 2002; 2003). While there is a large body of research on the Triassic ichthyosaurs of Svalbard, there are almost none on those from the Jurassic. Plesiosaurs have been studied to a limited extent too, but the only example of a Jurassic ichthyosaur is a rostrum assigned to Brachypterygius (Angst et al. 2010).

Cryopterygius kristiansenae

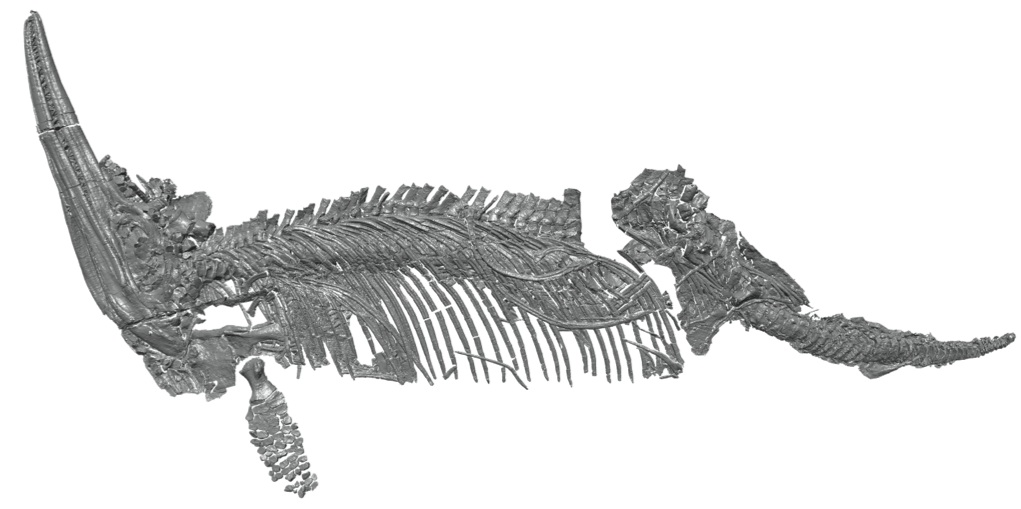

This new genus and species, Cryopterygius kristiansenae, is a large ichthyosaur, especially for the Late Jurassic, about 5.5 m long. Many features make this ichthyosaur different from others; the diagnosis takes up most of a column. What is great about this specimen is that it is very complete and exceptionally preserved—another of the papers in the issue is about the Slottsmøya Member lagerstätte, where this ichthyosaur was found. So, what makes this ichthyosaur different from others?

Well, there are mix of many small differences, which add up to quite a big difference, and many more noticeable. The differential diagnosis, where the important differences are set out, lists about 20 characters, three of which are unique among ichthyosaurs, or its closer family (autapomorphic): a distinct 90° angle at the posterior of the lachrymal, an element behind the quadratojugal with a ventral projection, V-shaped notch on the dorsal margin of the presacral neural spines. Another visible difference, and important from my point of view, is in the forepaddle. In Ophthalmosaurus, the humerus contacts three bones of the hands, and the same is found in Brachypterygius. However, in Cryopterygius, there are only two facets, for articulation with two bones. This is similar to that found in both the Lower Jurassic, such as Ichthyosaurus, but also in the Cretaceous Platypterygius. Also interesting is that the bones of the hand are clearly more polygonal than the British species from a similar time, although there is quite a bit of variation. The pelvis as usual, is small and does not contact the vertebral column. The ischiopubis has a prong that sticks out to the front, the gap between most likely allowed nerves to pass through.

Palvennia hoybergeti

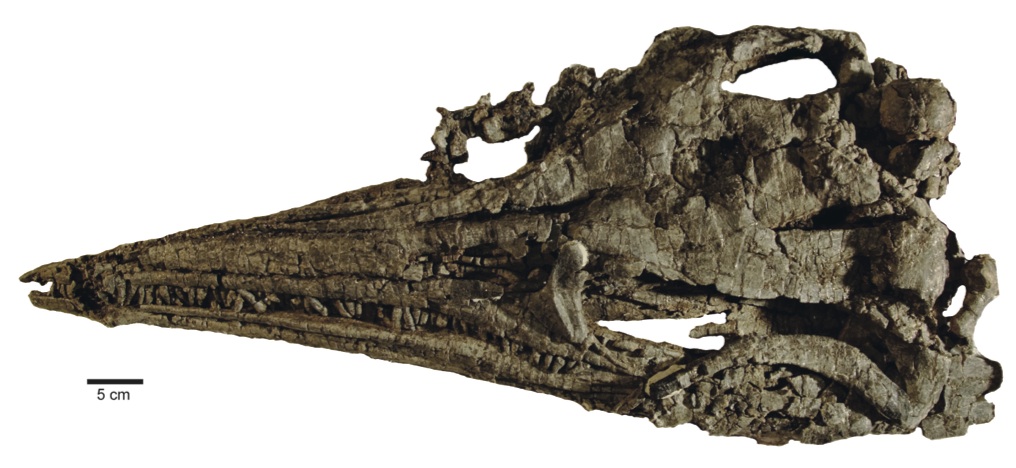

The other new ichthyosaur Palvennia hoybergeti, is not as complete as Cryopterygius: it is only know from a skull, and then you can only really see the top and bottom! This skull is over 80 cm, making Palvennia a medium- to large-sized ichthyosaur. The only autapomorphy is the very large pineal foramen, a hole in the top of the skull. However, Palvennia is also noteworthy in having a very high orbital ratio (McGowan 1976). This is a measure of the relative size of the eye, by comparing the size of the eye socket (orbit) to the length of the lower jaw. In Ophthalmosaurus, this ratio is 0.27: the eye is about ¼ the length of the lower jaw; Palvennia has an orbital ratio of 0.32, about ⅓ the length of the lower jaw.

And finally

This has been a brief overview of the ichthyosaurs themselves. The article (Druckenmiller et al. 2012) shows the images which I’ve used to illustrate, and has the full descriptions. There is also a lengthy comparison between Cryopterygius and Palvennia respectively and other ichthyosaurs from the Jurassic and Cretaceous. Cryopterygius is compared most closely to the Russian Undorosaurus, from a similar time, however the authors note that the validity of Undorosaurus is questionable. Palvennia on the other hand shows subtle differences and broad similarities to many coeval ichthyosaurs; the lack of material from behind the skull means that being more conclusive in comparisons is difficult.

References

ANGST, D., BUFFETAUT, E., TABOUELLE, J. and TONG, H. 2010. An ichthyosaur skull from the Late Jurassic of Svalbard. Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France, 181, 453–458.

BAUR, G. 1887. On the morphology and origin of the Ichthyopterygia. The American Naturalist, 21, 837–840.

COX, C. B. and SMITH, D. G. 1973. Review of Triassic vertebrate faunas of Svalbard. Geological Magazine, 110, 405–418.

DRUCKENMILLER, P. S., HURUM, J. H., KNUTSEN, E. M. and NAKREM, H. A.

- Two new ophthalmosaurids (Reptilia: Ichthyosauria) from the Agardhfjellet Formation (Upper Jurassic: Volgian/Tithonian), Svalbard, Norway. Norwegian Journal of Geology, 92, 311–339.

HULKE, J. W. 1873. Fossil vertebrate remains collected by the Swedish Expeditions to Spitzbergen in 1864 and 1868. Bihang till Kongliga Svenska Vetenskaps-Akademiens Handlingar, 1, 1–11.

MAISCH, M. W. and MATZKE, A. T. 2002. The skull of a large Lower Triassic ichthyosaur from Spitzbergen and its implications for the origin of the Ichthyosauria. Lethaia, 35, 250–256.

—— and —— 2003. Observations on Triassic ichthyosaurs. Part XII. A new Early Triassic ichthyosaur genus from Spitzbergen. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie—Abhandlungen, 229, 317–338.

MAZIN, J.-M. 1981. Grippia longirostris Wiman, 1929, un Ichthyopterygia primitif du Trias inférieur du Spitsberg. Bulletin de la Muséum National de Histoire Natural, Paris, Quartiéme Série, 3, 317–348.

—— 1983. Omphalosaurus nisseri (Wiman, 1910), un ichthyoptérygien à denture broyeuse du Trias moyen du Spitsberg. Bulletin de la Muséum National de Histoire Natural, Paris, Quartiéme Série, 5, 243–263.

MCGOWAN, C. 1976. The description and phenetic relationships of a new ichthyosaur genus from the Upper Jurassic of England. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 13, 668–683.

MERRIAM, J. C. 1911. Notes on the relationships of the marine saurian fauna described from the Triassic of Spitzbergen by Wiman. University of California, Bulletin of the Department of Geology, 6, 317–327.

SANDER, P. M. 1992. Cymbospondylus (Shastasauridae, Ichthyosauria) from the Middle Triassic of Spitsbergen: filling a paleobiogeographic gap. Journal of Paleontology, 66, 332–337.

—— 1998. New finds of Omphalosaurus and a review of Triassic ichthyosaur paleobiogeography. Paläontologische Zeitschrift.

WIMAN, C. 1910. Ichthyosaurier aus der Trias Spitzbergens. Bulletin of the Geological Institute of Upsala, 10, 124–148.

—— 1929. Eine neue marine Reptilien-Ordnung aus der Trias Spitzbergens. Bulletin of the Geological Institute of Upsala, 22, 1–14.

Leave a comment