Ichthyosaurs: what are they?

Well, I had planned to write once every week or so, but, as you can see, that hasn’t gone to plan so far. In theory that should mean that I have a significant amount to write about now, but…

Since last posting, I have (finally) begun my PhD at Bristol University, and after two weeks at university I had finally done a plan for my study; at least the first two years. I have also completed a funding proposal to the Palaeontological Association to allow me to visit some museums. This does mean that over the past seven weeks I have actually written something down! which hadn’t happened in the previous four months. Other than that, most of my time has been spent finding papers to read, and then reading them.

Now is probably a good time to start going through some of the basics of my research project. The title of the project is ‘Ichthyosaurs of the Late Jurassic’, and I will describe the two main constituents of that title in this and the next post; starting with ichthyosaurs.

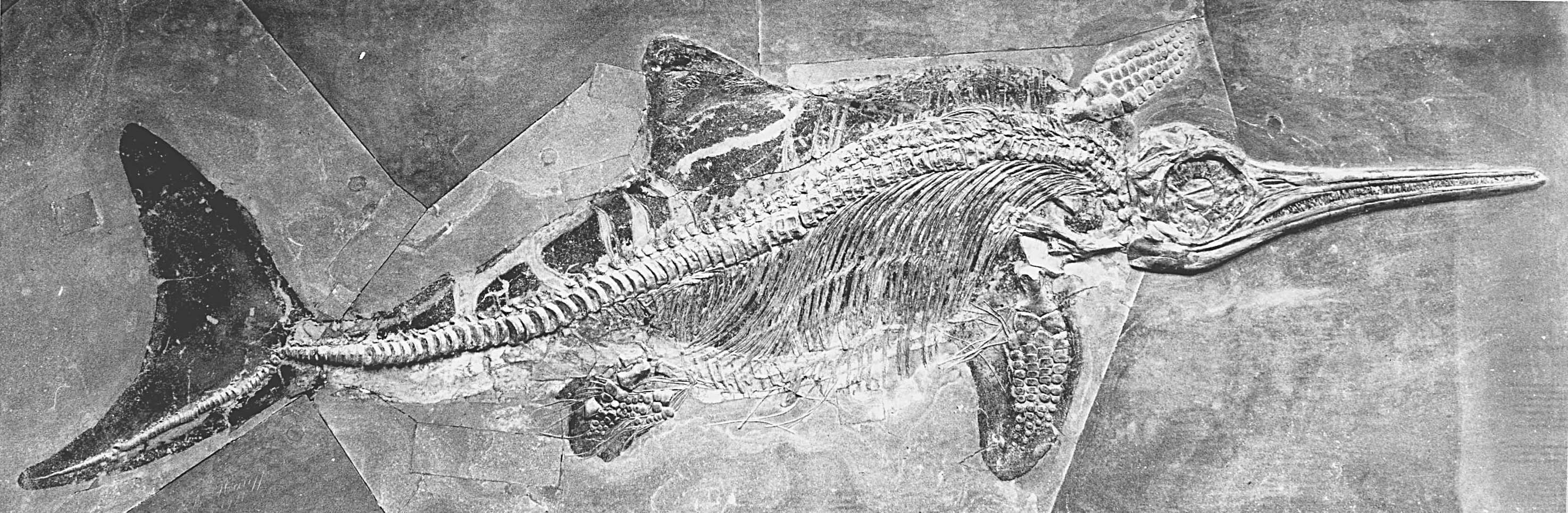

The name ‘ichthyosaur’ (ICK-THEE-o-SAWR) comes from the Greek ‘ichthyos’, meaning fish, and ‘sauros’, meaning lizard, so they are ‘fish lizards.’ This name was assigned for this group of animals based upon their striking similarity to fish (see below). The group, or clade, to which ichthyosaurs belong is variously called Ichthyopterygia or Ichthyosauria and contains 49 valid genera and 75 valid species. (Maisch 2010). As seen from the photo, ichthyosaurs have an elongate, narrow jaw; occasionally large eyes; four paddle-like limbs, with the forelimbs larger than the hindlimbs, formed by many tessellating finger/foot bones; tail fin defined by a ‘kink’ (apex) it the backbone, with vertebrae on the ventral (frontside) edge (McGowan and Motani 2003).

Ichthyosaurs first appeared in the Lower Triassic (~240 million years ago) as already specialised aquatic animals, probably also with live birth too. This sudden appearance as such a derived animal has led to much debate over ichthyosaurs origins and how they are related to other vertebrates. It has been variously suggested that ichthyosaurs are related to the early amphibians and turtles before more recently settling upon a diapsid (a group comprising , among others, lizards, dinosaurs and birds) origin. Maisch’s (2010) recent attempt to resolve this using two high profile amniote datasets remains places Ichthyosauria within diapsids but is not conclusive on the relationships within.

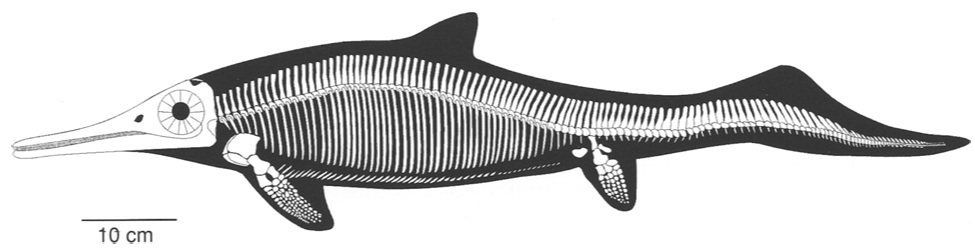

Triassic ichthyosaurs (e.g. Mixosaurus below, skeletal reconstructions from Sander (2000)) have been the main focus of ichthyosaurs study over the past 30 years as new finds, especially from China, have been uncovered. These earlier ichthyosaurs, although already highly derived, show a definite progression of evolution through the Triassic. The most distinctive differences are having more similarly sized fore- and hindlimbs and more elongate tail with less defined apex.

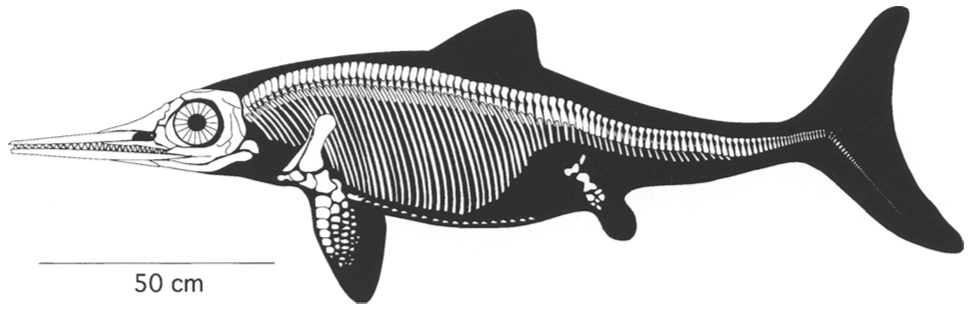

Following a mass extinction at the end of the Triassic (~200 million years ago), ichthyosaurs with a different form became dominant. These thunniform (literally ‘tuna-shaped’) ichthyosaurs (e.g. Stenopterygius below) include the famous species Ichthyosaurus, from the Lias rocks of Lyme Regis in Dorset, England, and Stenopterygius from the Posidonienschiefer of southwest Germany which have both been found in huge abundances. The thunniform ichthyosaurs had the more characteristic fusiform shape, much larger forelimbs and crescent-shaped tail fin. This morphology is found in all ichthyosaurs until they became extinct. In the Early Jurassic (~200–~170 million years ago) there was a particularly high diversity, although many of these had a very similar body plan, and so disparity was lower compared to the Late Triassic (Thorne, Ruta and Benton 2011).

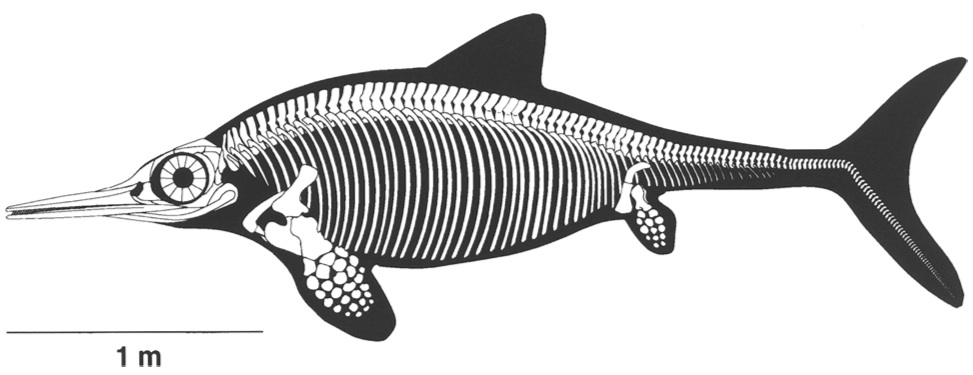

In the Middle and Late Jurassic (~170–~145 million years ago) the diversity of ichthyosaurs decreased: the Late Jurassic hosts only ~7 species. Many of these are known only from a few specimens, however Ophthalmosaurus (see image below), from the Oxfordian (~160–~155 million years ago) of Europe and America, is know from hundreds of specimens, particularly from the Leeds collection housed dominantly in the Natural History Museum in London. Ophthalmosaurus means ‘eye lizard’ and is so named because it has the largest eye relative to its body size of any known animal. The Cretaceous (144–65.5 million years ago) ichthyosaurs are almost entirely contained within the genus Platypterygius. This ichthyosaur has been found worldwide, from Australia to America to the United Kingdom.

The ichthyosaurs became extinct in the middle of the Cretaceous (~90 million years ago), about 30 million years before the dinosaurs. The reasons for this are unknown and has been hotly debated. At the same time there were many small extinction events occurring. Ichthyosaurs were also not very diverse (only Platypterygius remained). Competition from other groups had increased, particularly with the appearance of mosasaurs, which had a somewhat similar morphology. It is most like that a combination of these caused the ichthyosaur’s demise.

This has been a, rather long, summary of ichthyosaur evolution through their existence. Hopefully it has been comprehensible and informative. Soon (and I mean soon), I will write a basic introduction to geological time (explaining the difference between Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous). After that I plan to describe my PhD plan in more detail and then go on to more specifics of ichthyosaurs: what we know, what we think we do, and what we simply don’t.

References

MAISCH, M. W. 2010. Phylogeny, systematics, and origin of the Ichthyosauria—the state of the art. Palaeodiversity, 3, 151–214.

MCGOWAN, C. and MOTANI, R. 2003. Ichthyopterygia. In SUES, H.-D. (ed.) Handbook of Paleoherpetology, Vol. 8. Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil, Munich, 175 pp.

SANDER, P. M. 2000. Ichthyosauria: their diversity, distribution, and phylogeny. Paläontologische Zeitschrift, 74, 1–35.

THORNE, P. M., RUTA, M. and BENTON, M. J. 2011. Resetting the evolution of marine reptiles at the Triassic-Jurassic boundary. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108, 8339–8344.

Leave a comment